Peru

“Attach great importance to the indigenous population of America…

They will become so illumined as to enlighten the whole world.”

– ‘Abdu’l-Bahá

After a year living in the Andes of Peru (teaching at the national university, learning the language, making local friends) I see how I can introduce a theatre project in rural Puno. With a local friend, Efrain Miranda (a Bahá’í of Quechua descent) and fellow North American, Carol Braun, we conceive El Teatro de Pan y Paz (Bread and Peace Theatre). Our troupe’s name reflects the Bahá’í practice of cultivating spirit and service in addressing spiritual as well as material needs.

“For man two wings are necessary.One wing is physical power and material civilization;the other is spiritual power and divine civilization.With one wing only, flight is impossible.”– ‘Abdu’l-Bahá

We begin with a project budget of four hundred dollars (contributed by three donors in the States). I have written a play in Spanish, so we arrange readings to get feedback from local Peruvians. Then we proceed with a cadre of local, interested youth, every afternoon, to make puppets, masks and stilts on the roof of my apartment. This means of fellowship for the youth doubles as a service activity. They feel empowered while having fun.

We are working hard to be ready for the theatre institute we have planned for the January school vacation. With the blessings of the National Spiritual Assembly of the Bahá’ís of Peru, we use the facilities of Radio Bahá’í of Lake Titicaca to house, feed and train twenty youth over a week-long period. Some come from the Peruvian cities of Lima and Arequipa, but more than half are local indigenous youth.

Morning classes are for studying the goals of the United Nations’ International Year of Youth (1985) and the possibilities and purposes of theatre. I give most of the classes, but an Auxiliary Board member and NSA member also are invited to address the youth. After lunch each day we rehearse the play I’ve written and construct the materials (masks, costumes, big puppet, Inca sun) necessary for the production.

Making the Inca sun from mud & papier-mâché

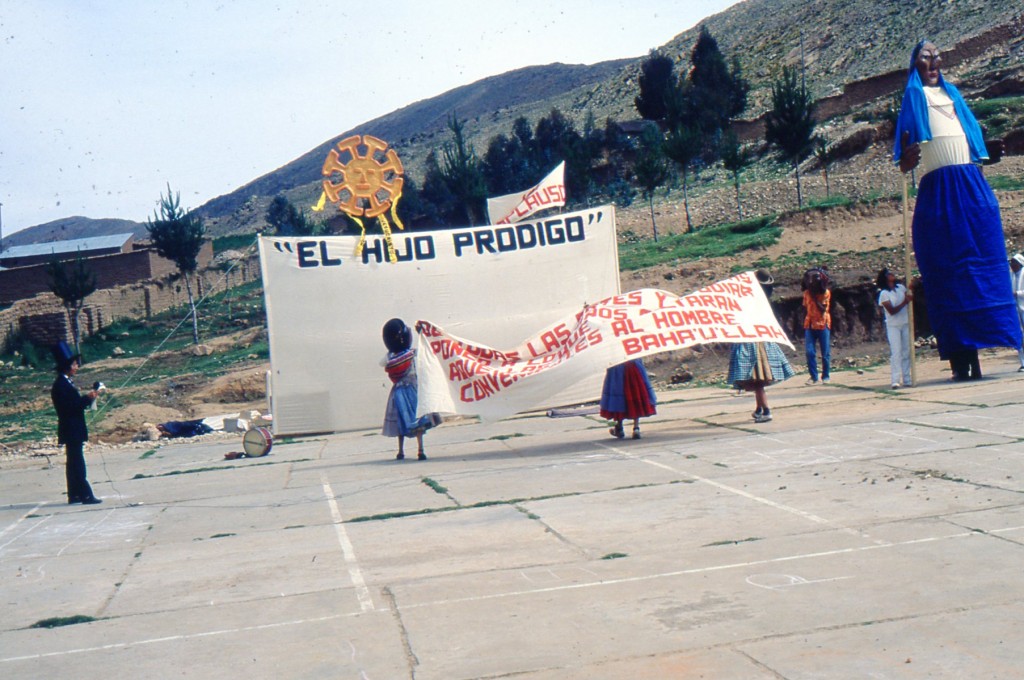

Since Peru is a Catholic country, the play, El Hijo Prodigo (The Prodigal Son) uses a biblical parable in modern context. Namely, to be educated in much of the Third World is to go increasingly farther from one’s village in order to receive the best education. In this broad, brush-stroke play (of placards, drum rolls, full head masks and a 15-foot high puppet) the peripatetic “prodigal” son, allured by city pleasures, fails to return home to his village when he graduates from university. The family is broken up, but the youth has a job. What’s to be done? The play raises that question, but then, only suggesting some answers, allows the audience to consult about resolving the conflict.

The playwright as Master of Ceremonies

The use of a Master of Ceremonies eliminates the need for dialogue between characters. This “stage manager” Narrator explains and presents the dramatic story to the audience — and even helps actors with props. The fact that the amateur performers do not need to memorize lines reduces their self-consciousness. Full head masks also allow amateur actors to be anonymous (as well as males to play females and vice versa) On the last day of the Theatre Institute, our newly formed troupe stages its first production of El Hijo Prodigo. After that week, we take the play to Andean villages, performing under open skies. Blurring the line between audience and cast, we invite local people to hold signs or to participate in the opening procession. [click here to read script]

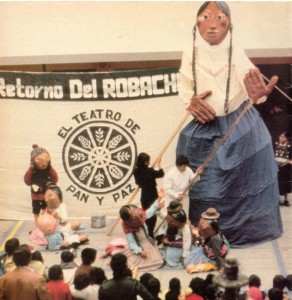

I next write a play addressing another social issue. This time, instead of a biblical parable, I use a local legend for my story line. Because so many rural children die of dehydration (induced by diarrhea), the indigenous mothers speak of a diabolical baby snatcher. In El Retorno del Robachicos (“The Return of the Baby Snatcher”), the villainous title character (whom the audience is encouraged to boo) personifies poor hygiene.

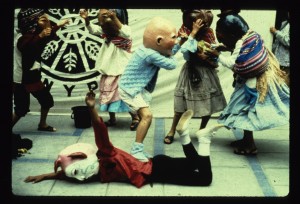

Some young mothers in full-head masks (the “chorus”) backbite about a new mother whose child is dehydrated and dying. But when their babies also become ill, these women stop gossiping and unite with the distressed mother against their common foe. At the play’s climax, when the villainous Baby Snatcher is about to capture the ill (and fleeing) child, the drum roll sounds and the cymbals clash. While all characters freeze on stage, an enormous head mask rises slowly behind the scrim. As the audience looks on in hushed awe, the body and hands of this enormous puppet also rise.

The 15-foot high puppet then walks out from behind the scrim (two troupe members under her skirts manipulate her movement, while two other members move each hand as she speaks — via the Narrator). It is La Curandera, the village healer, with “weapons” — the Narrator explains — to prevent dehydration and defeat the Baby Snatcher. In a comic scene, the baby ducks under the big puppet’s skirts and comes out fighting with the “weapons” (boiled water, breast feeding). An enormous hypodermic needle for vaccinations is the villain’s ultimate undoing. The neighbors cheer and celebrate.

During the finale, the baby’s parents make an oral rehydration serum. Making it out of local foods, the Charlie Chaplin-esque husband humorously shows how fathers can help too. At the end of the performance, the youth of El Teatro de Pan y Paz distribute cards with the rehydration recipe.

During the finale, the baby’s parents make an oral rehydration serum. Making it out of local foods, the Charlie Chaplin-esque husband humorously shows how fathers can help too. At the end of the performance, the youth of El Teatro de Pan y Paz distribute cards with the rehydration recipe.

That July we are invited to perform at the International Youth Conference held in Lima. [click here to read script]