OFF-BROADWAY

“Yogi is one of a kind, and it’s too bad.”

—Joe DiMaggio

Evil is sexy. Villains thrill us. Macbeth and Darth Vader, like train wrecks, enthrall us. We smile at the cunning of Richard III and recall the stalking killer in No Country For Old Men more than its would-be hero (Do we even recall his kindness — returning to give water to a dying man — triggers his misfortune?). Are we fascinated by evil because goodness is less recognizable, less part of our daily lives than self-involved craving? Even when a writer sets out to celebrate the godly, like Milton with Paradise Lost, Satan steals the show. Claggart eclipses Melville’s Billy Budd, and Ahab his Moby Dick. So what’s a writer to do? Go over to the dark side, and portray only its violence and vanity? After all, Pollyannas aren’t believable. Shakespeare’s Henry V is a marble statue to admire, not the fun he was partying as practical joker Prince Hal. Few writers can dramatize the good as well as Matthew, Mark, Luke and John. Then again, truth is stranger than fiction. So writers wanting to reflect all of life, not just its selfish baseness, often turn to the archetype of the holy fool. Many a truthful word can only be said in jest. By making a life of chivalry laughable with his idealistic Don Quixote, Cervantes reminds readers of what little they settle for as pragmatic realists. By creating a Christ-like protagonist and a society that snickers at the selfless, Dostoevsky raises doubts about for whom his novel The Idiot is named.

For decades I struggled with the challenge of creating a noble protagonist who wasn’t boring — with scant success. Finally, the archetype of the holy fool — and the truism that life is stranger than fiction — graced me with opportunity. Some people know Yogi Berra for his Hall of Fame baseball playing, others know him for his wacky yet wise sayings, but few know why “Yogi Berra is a national treasure. Every time I see him,” says former American League President Bobby Brown, “I feel a little better about the human race.” “It felt like he was kind of a baseball ET,” says ex-Yankee captain Don Mattingly. “He could make his finger light up and you too.”

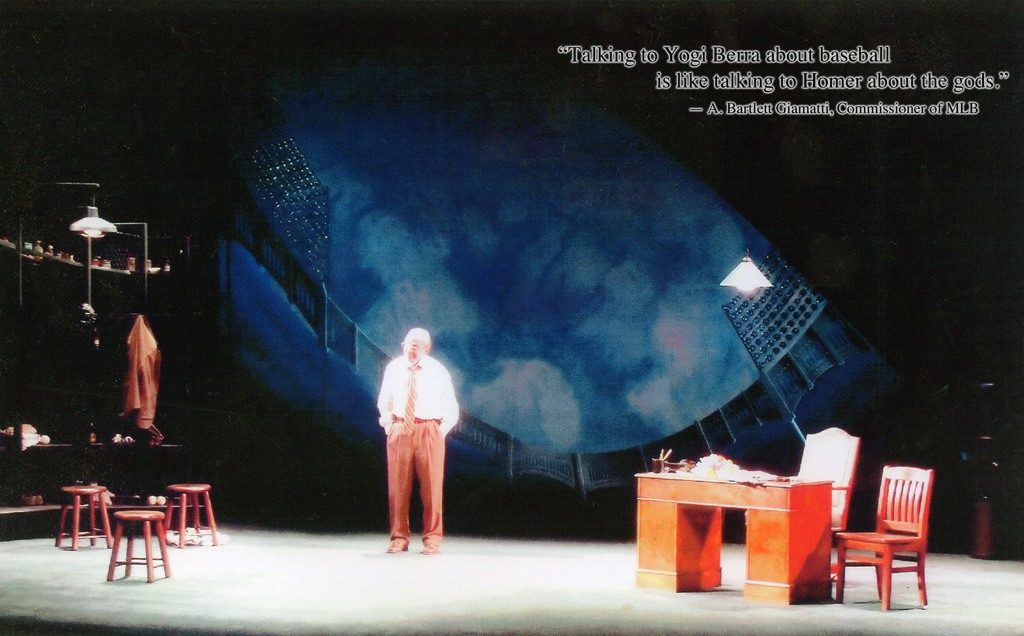

In 1985, only 16 games into the baseball season, New York Yankees owner George Steinbrenner fired Yogi as manager of the team. Some people say baseball needed George Steinbrenner the way Jesus needed Judas. Not Yogi. He’d call that remark a cheap shot. Yogi Berra doesn’t backbite. If a person badmouths somebody in his presence, he shrugs, “Who’s to say?” and walks away. Yogi also doesn’t hold a grudge. So why then, after Steinbrenner fired him, did Yogi vow never to return to Yankee Stadium so long as George was owner of the team? And he didn’t. Not for fourteen years. What so hurt or angered that Yoda of a Yankee that he held a grudge until 1999? That’s the dramatic question. Wrapped in the chocolate of comedy, that nougat gets chewed on in my play. Down in the catacombs of the clubhouse of Yankee Stadium — that cathedral of baseball — Yogi nervously prepares for his homecoming speech. While the ghosts of the Yankee greats whisper to him, Yogi comes to grips with what sent him into exile and what really brought him home again.

“Fair is foul,” say the witches in Macbeth, “and foul is fair.” Not in baseball. Situational ethics make for lousy ground rules. Yogi reminds us of the only infallible umpire in life. After showing us how to play ball in the only game that has no definitive ending, on the only playing field that stretches toward infinity, Yogi now shows us how to play out the narrow game of our own brief lives.

“He’s one of those Christmas Eve guys… He’d do anything for you. He’d give you half of whatever he had.”

—Joe Garagiola

you don’t like your wife.”

—Don Zimmer