India

“India is the only millionaire…” “…without India no worthwhile scientific discovery could have been made.”

— Mark Twain — Albert Einstein

“On the face of India are the tender expressions which carry the mark of the Creator’s hand.”

— George Bernard Shaw

2004-06

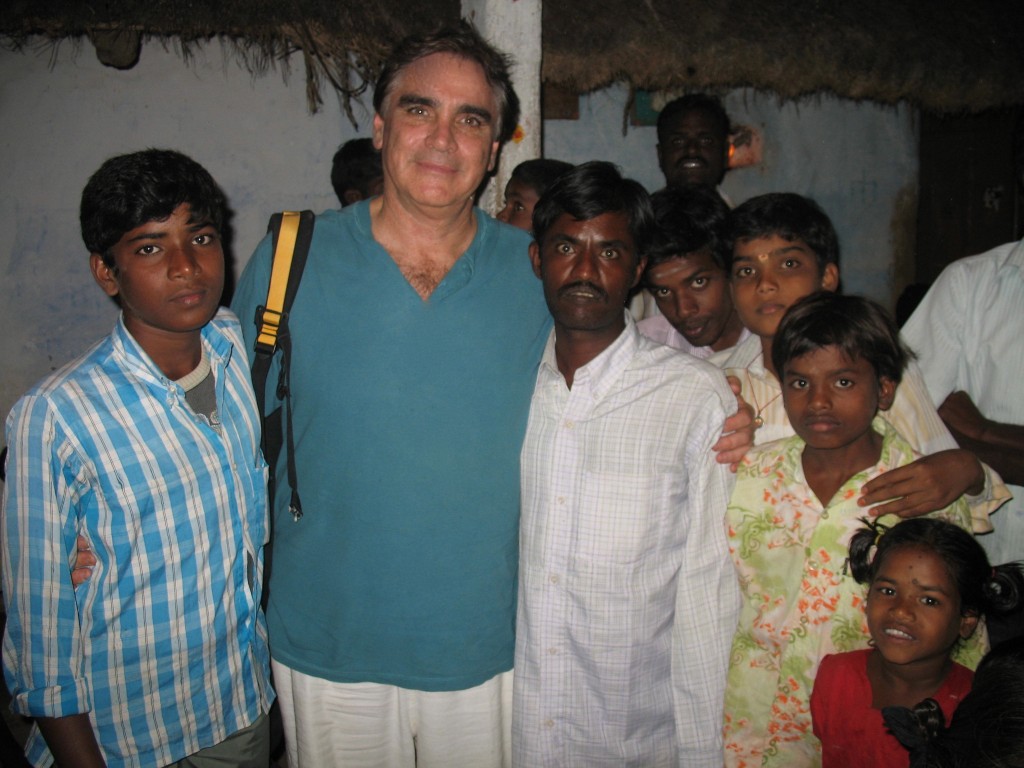

Alex Frame, the producer of the 1992 World Congress in New York City, calls and asks me to join him in India. The Office of Social and Economic Development at the Bahá’í World Centre wants to launch a theatre project in the southern state of Tamil Nadu “to explore the potential contribution of traditional forms of theatre, especially puppetry” in support of the institute process.

In November Alex and I meet in New Delhi and then fly 1500 miles to Chennai, the capital of Tamil Nadu. We’re met at the airport with garlands of flowers presented by two Auxiliary Board members and the Regional Council Secretary. Then the five of us drive inland for three hours to the town of TvMalai (Thiruvannamalai). When we arrive at the local Bahá’í Center, a flower-strewn path greets us. As soon as we are seated inside, two little girls in colorful saris perform a traditional welcome dance for us.

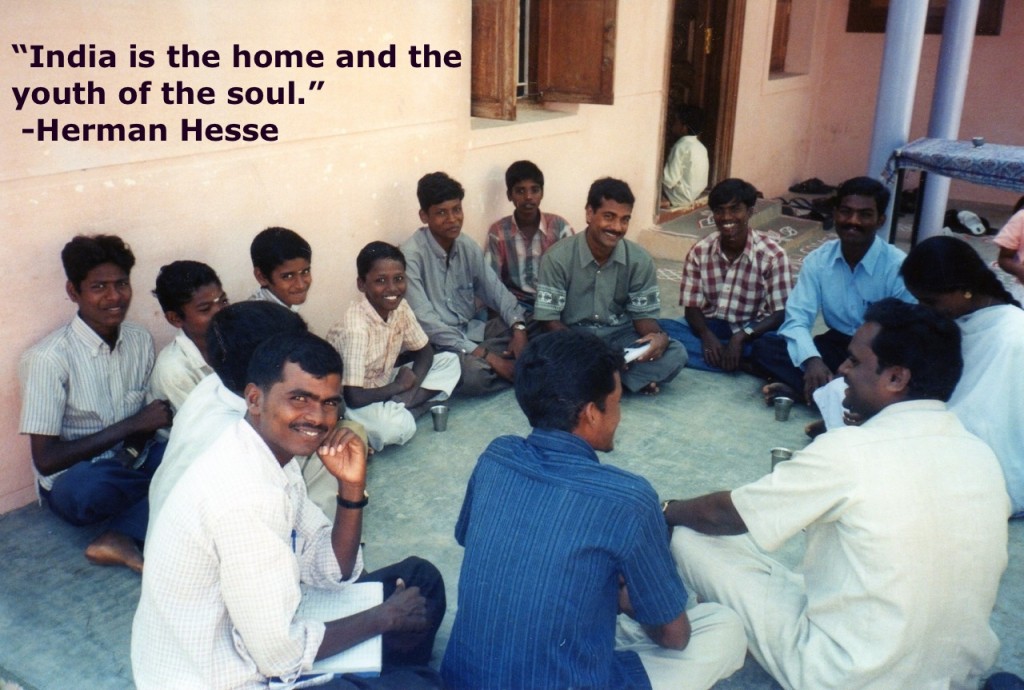

Alex expresses gratitude and praises the friends for all they’ve accomplished with study circles, devotionals and children’s classes. He then addresses our purpose for being there. He explains the Universal House of Justice’s emphasis on “puppetry.” While Alex speaks, I glance at a bulletin board that has a chart indicating the numbers of local people who have completed each Ruhi book: a hundred in this village, a hundred and fifty in that village… I’m astounded. Alex then asks me to speak. I explain that “sacred theatre” is the integrating of the various arts — story telling, music, movement, visual imagery, and the Sacred Word — to attract hearts. I point out that no one with specialized artistic talent or experience is required. One need not even speak the same language as one’s audience. I point out the power and purpose of creating sacred space at Feasts or at any devotional gathering. I also briefly talk about social drama: health issue plays, for example, that serve to educate the community, and how such drama can be performed in an entertaining manner. We then ask the friends to divide into two groups to consult about their community needs.

Alex expresses gratitude and praises the friends for all they’ve accomplished with study circles, devotionals and children’s classes. He then addresses our purpose for being there. He explains the Universal House of Justice’s emphasis on “puppetry.” While Alex speaks, I glance at a bulletin board that has a chart indicating the numbers of local people who have completed each Ruhi book: a hundred in this village, a hundred and fifty in that village… I’m astounded. Alex then asks me to speak. I explain that “sacred theatre” is the integrating of the various arts — story telling, music, movement, visual imagery, and the Sacred Word — to attract hearts. I point out that no one with specialized artistic talent or experience is required. One need not even speak the same language as one’s audience. I point out the power and purpose of creating sacred space at Feasts or at any devotional gathering. I also briefly talk about social drama: health issue plays, for example, that serve to educate the community, and how such drama can be performed in an entertaining manner. We then ask the friends to divide into two groups to consult about their community needs.

When we re-convene as one group, we list the two groups’ goals on the board: to use arts in children’s classes; to improve the quality of 19-Day feast; to assist junior youth in helping others learn about health and education issues, etc. We point out how the process of learning how to create sacred space can meet more than half of these goals. The resulting infusion of spirit will then motivate them to find ways to meet the other goals.

The following morning via opening devotions, Alex and I model how music and story telling create the receptive “sacred space” for moving hearts. The first session then introduces the basis of all theatre: story telling. Since few of the TvMalai friends own books, but all have access to the Ruhi workbooks of the Bahá’í institute process, we focus on four stories found in Ruhi book #4, The Twin Manifestations. I tell the story of Bahá’u’lláh’s teaching the Bábís to chant in the Síyáh-Chál. We all sing that anthem. Then I ask for a volunteer to re-tell the story. One does. Has she left out any details? Some say yes, and mention which details. Then someone else tells the story. We praise the good memories they have and point out the exemplary story-telling skills that were demonstrated. Next we introduce the story of the Bábís exile to ‘Akká. I detail the suffering, the sickness, and the hunger. I then ask someone to re-tell the story. Other friends point out the details that were left out. Another workshop participant offers to re-tell the story. Afterward Alex and I address elocution and animation in story telling.

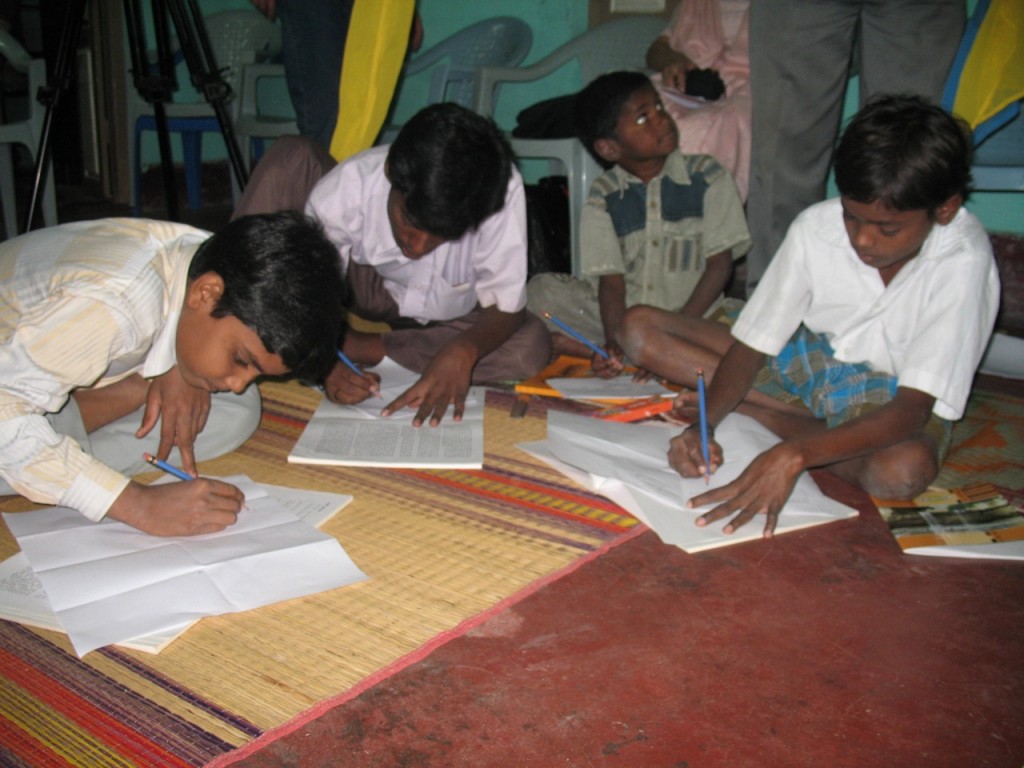

We then introduce how to make “storyboards” [see Storytelling link under “Resources”]. First, we ask the participants to choose one of the four stories that were recounted. After doing so, we divide them into four groups, one group for each story. Each participant is then given a large piece of paper and asked to fold it into 12 or 16 parts. Each storyteller is to identity the major “beats” of her chosen story, and then, in each little box, to draw some image so that, when they glance at it, they will remember the details for telling their story.

Sketching Storyboards

The idea is that after making the storyboards, one can practice his or her story with a fellow participant. They are to practice with a partner until the storyboard is no longer necessary. Everyone goes off with his group and each member of each group makes a storyboard.

Afterward when we re-convene, some storyboards are so beautifully detailed we hang them up. This paves the way for the next day’s opening session about the role of the “visual arts” in theatre — the use of signs, back drops, and of course, puppets. But first we ask each group to work together that evening to determine how best they can present their story — as a group — the next day. We remind them of all the elements of theatre at their disposal — music, movement, narration, visual arts — and, of course, the Creative Word.

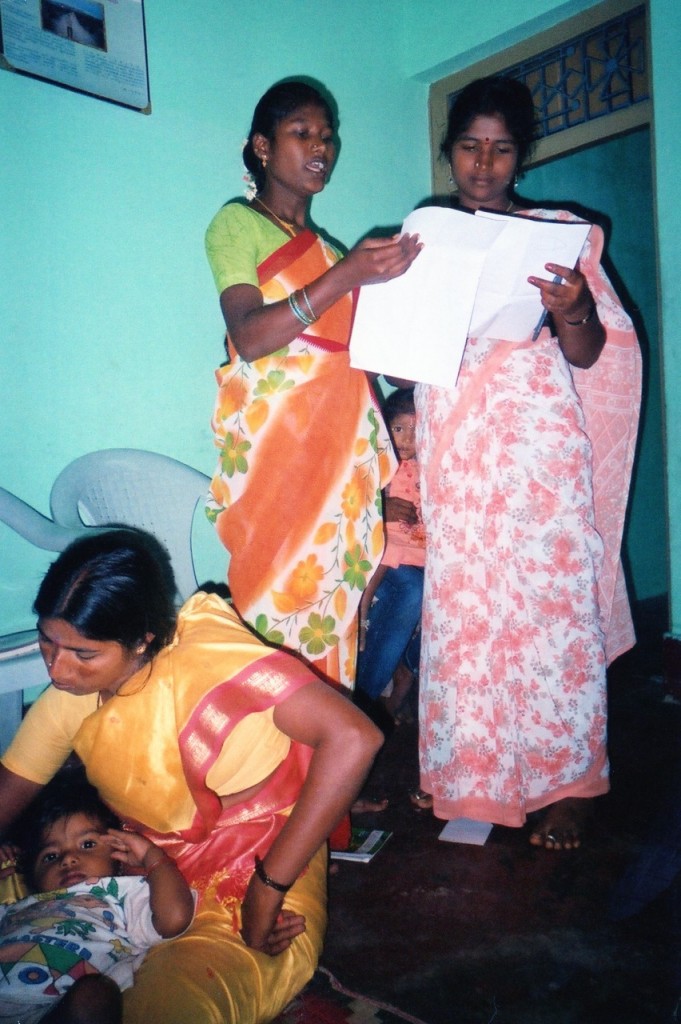

That night I cannot sleep, and it’s not the sign in my hotel room saying, “Keep windows closed and monkeys out.” I fear that I fumbled through my presentation and gave too much information. But the next morning when Alex and I arrive at the center, a smiling middle-aged woman greets us and says she has something to show us. She sits us down, and then, she and the seven members of her story group sit cross-legged on the floor in two rows. Two members have percussion instruments and the middle-aged woman is holding what looks like an enormous bow for shooting oversized arrows. She starts to strum it and, as percussion instruments tap out a beat, she tells the story of Bahá’u’lláh’s imprisonment in the Síyáh-Chál dungeon. As I watch I think this is what Homer must have looked like, strumming a lyre while recounting The Odyssey.

Villu Pattu (Bow Song) Storytelling

As this radiant woman recites and plucks her twangy bow, others in her group exclaim in response, calling out like a congregation in an African-American revival church. Some responses are questions about the story (“They woke up the Shah?” “They chanted all night?”) This technique dramatizes and underlines the story line. Alex and I look at each other in amazement. The Tamil friends are using their traditional arts to support the institute process. This musical bow instrument is part of what local Indians call “villu pattu” (a bow song), a traditional Tamil method of story telling. However, instead of recounting traditional Hindu tales of Krishna, they are telling stories about the dawn of the New Day.

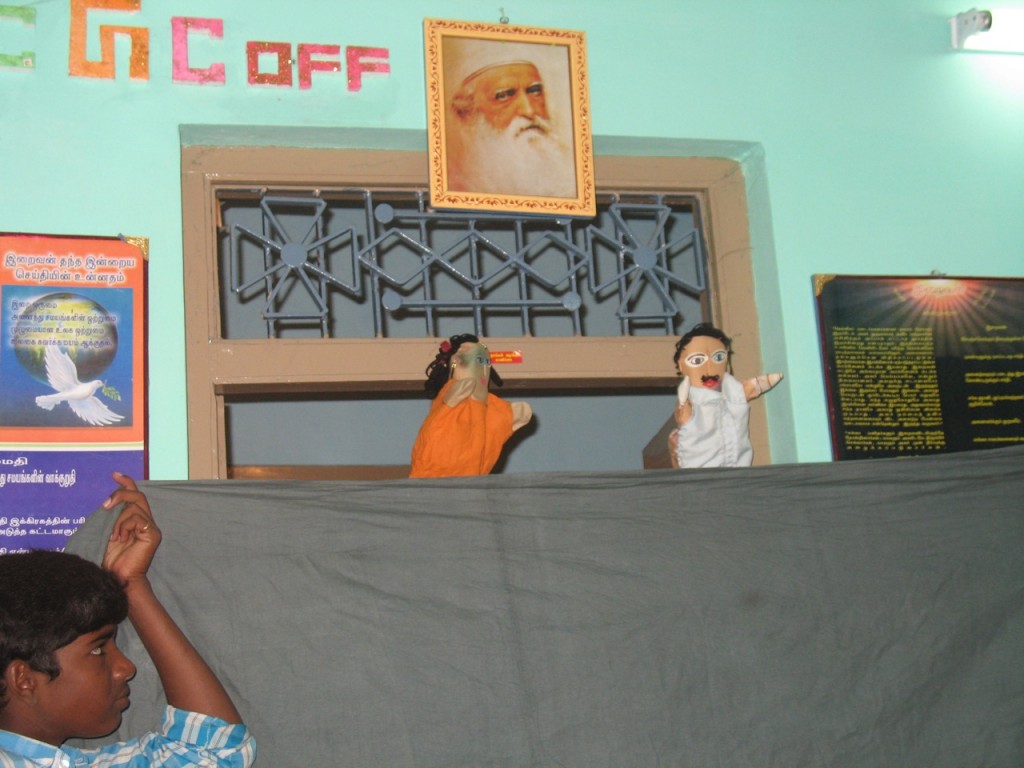

The previous afternoon the face of a quiet, young man had lit up at Alex’s mention of puppets. Now he displays two hand puppets he made over night. He has them perform a welcome dance above a scrim to introduce a second group’s story.  The talent and enthusiasm of the TvMalai friends astound us. Alex and I leave India both humbled and inspired.

The talent and enthusiasm of the TvMalai friends astound us. Alex and I leave India both humbled and inspired.

Three weeks later the tsunami of Christmas 2004 hits Chennai. Despite the ensuing devastation and hardships, Alex and I begin receiving reports of hundreds of musical/story-telling devotionals occurring in the villages of TvMalai. Meanwhile, I write a play about the tsunami called Waves of One Sea. It’s a social drama in the same vein as my Peruvian plays. [read complete script here] Perhaps when Alex and I return we will expand the project from sacred theatre to social drama.

Four months later we arrive at the Chennai airport and are driven straight to a village three hours inland. The local Bahá’ís are scheduled to perform a “villu pattu” bow song. Come evening when we arrive at the village, hundreds of people are gathering. The van can barely inch its way to the site. A generator is used for lights and for amplifying sound. Standing amidst the crush of the crowd, I watch the indefatigable young man who loves puppets. To recorded music he choreographs his hand puppets above a curtain in a traditional welcome dance. Then the “villu pattu” bow song begins.  At the end of the musically told story, various dances are performed. After the dances, the audience is invited to attend study circles, children’s classes and devotionals.

At the end of the musically told story, various dances are performed. After the dances, the audience is invited to attend study circles, children’s classes and devotionals.

The next morning rather than introduce something new, Alex and I decide to build on the group’s story telling success. I put Waves of One Sea aside and demonstrate how to evolve their four stories into dramatic performances. I discuss the five “beats” to most story arcs: the set-up, the rising conflict, the crisis, the face-off and the resolution. I break down each of the four stories from Ruhi Book #4 into these five components, so participants have a sense of the “dramatic arc” of each story [see Storytelling link under “Resources”]. Then the workshop participants divide themselves into four groups, each group once again for one of the four stories. They are to consult about how they might present their story — using elements of music, movement, torches, visual arts, puppets, live actors, etc. They then are to assign tasks toward achieving their goal: who in their group is to act or narrate, who will find materials for torches or puppets, who will make what, etc. Simple musical instruments are made available, and we encourage the groups to include music — recorded or live — as part of their performance. At the same time, we discourage the use of dialogue in favor of a Narrator. The three groups are then to rehearse and perform their presentations later in the week.

After each group’s consultation, individuals begin preparing and creating their materials. Mud for making masks is lugged to the center;

Old newspapers for papier-mâché are gathered.

Old broom sticks, coffee cans, and sand for making torches are found.

Síyáh-Chál chain links are made out of construction paper.  The final afternoon when they perform their stories, Alex and I are once again impressed by their artistic staging. Signs and puppets appear from behind a scrim,

The final afternoon when they perform their stories, Alex and I are once again impressed by their artistic staging. Signs and puppets appear from behind a scrim,  a narrator introduces the story, characters pantomime the roles with stylized movements, seated Bábí prisoners chant and awaken a sleeping Shah.

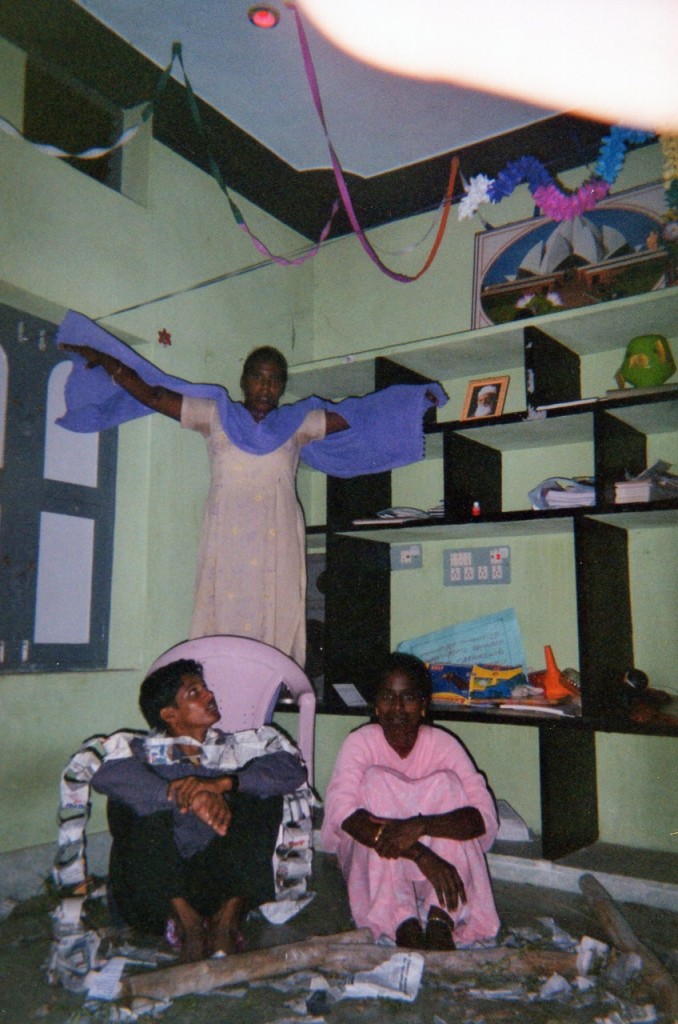

a narrator introduces the story, characters pantomime the roles with stylized movements, seated Bábí prisoners chant and awaken a sleeping Shah.  Torches, streamers and other visuals are employed, and once again local theatre traditions are incorporated into the performance.

Torches, streamers and other visuals are employed, and once again local theatre traditions are incorporated into the performance.

After Táhirih unveils her face at Badasht…

…all the actors freeze, while a young girl does a Tamil dance of celebration.

As Alex and I head for the Chennai Airport, we happily feel we have rendered ourselves superfluous — the project is well in the hands of the local friends. Four months later we hear they have organized a puppetry workshop in Chennai. It opens with two puppets wondering aloud why all these people have come together from the villages. To a puppet workshop? Why? They can’t understand why people would spend so much time learning about puppets. Aren’t puppets just for children? The weekend workshop provides a compelling answer: demonstrating how puppets and theater advance the institute process of community building.